|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

Search VALEP

|

|

|

Filter

Filter 1

Filter 2

Table of Content

Chapter

Section

...

The content of this section changes depending on the datatype and offers different filter criteria. In the case of HTML documents this window will also provide a table of contents.

Archives

ASP Archive

Carnap Collection

Box 23

Folder 5

DSC_7585

DSC_7586

...

Example 1: Author text (Carnap's Diaries)

1 Tagebuch 14. II. 1908 - 13. V. 1908

Tagebuch von 1908

Der Vorsatz, ein Tagebuch zu schreiben, in dem Sinne, wie ich’s jetzt

meine, mag wohl schon ein Jahr oder noch älter sein. Auch in letzter

Zeit habe ich wiederholt gelesen, dass es äußerst nützlich und angenehm

ist, wenn man in späteren Zeiten sehen kann, was und wie man früher

gedacht hat. Deshalb sollen bei mir die Erlebnisse in den Hintergrund

treten. Ich möchte gern später ein skizzenhaftes Bild von meinem

Gedankenleben, besonders der Entwicklung, den Fortschritten in meinem

geistigen Leben haben. Später sollen mich diese Zeilen daran erinnern,

was ich für eine Weltanschauung, was für eine Anschauung über manches

Philosophische, was mir jetzt oder schon früher aufgestiegen ist, und

noch über vieles andere ich gehabt habe, und wie sich alles das im Laufe

der Zeit weiterentwickelt hat. Ich habe schon vor Jahren manchmal bei

kleinen Kindern beobachtet, dass sie oft allerlei denken und meinen und

überlegen und philosophieren, wovon sie nichts oder nur wenig oder nur

ein schattenhaftes Spiegelbild in ihren Worten dartun. Woher habe ich

dann gewusst, was sie dachten. Ich weiß es nicht mehr genau, oft fielen

mir meine Gedanken ein, die ich in im Kindesalter in meinem

Köpfchen gedreht hatte und fast alle mit nur mit wenigen

Ausnahmen wieder vergessen habe. Da dachte ich, wenn ich

2 Tagebuch 24. III. 1910 - 4. V. 1910

|

|

|

Onkel Wilhelm |

||

|

Vormittags 530 - 8 nach Pylos. 10 - 12 nach Pygros, 12 2 - 6 nach Patras.

12h Mitternacht - 5 Patras. - Itea, 6 - 9 Itea - Kastri

Apollobezirk, Museum; Gymnasion, Marmaria; abends kommt

Schwarzschild

Aprilscherz mit dem Ei; Agnes'

10 - 4 über den Parnass nach Arachowa.

1/2 7 - 1/2 3 nach Chäroneia; 3 - 1/2 8 nach Athen.

Brief von Agnes

Gräberstraße, Dipylon, Statuen des Apollos und Hadrian, Markt mit Tor, Turm der Winde; Philopappos.

Museum; Onkel Wilhelm

Nationalfest; Philopappos.

Eleusis; Akropolis.

30 Tagebuch 1. VII. 1927 - 28. XII. 1927

Über Entscheidbarkeit der Arithmetik gearbeitet.

Gearbeitet über Entscheidbarkeit.

Abends zu Maja

5 Schlick

Abends mit Wittgenstein

Abends Diskussionsabend: Realität des Fremdpsychischen. Roffenstein

Mittags mit Schlick

Nachmittags zur Frau Neurath

Example 2: Letter

2

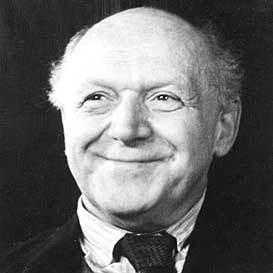

Neurath an Carnap, Wien, 31. Dezember 1927

Otto Neurath an Rudolf Carnap, Wien, 31. Dezember 1927

Dezember 1927

Gute Grüße, frohe Weihnachtswünsche von mir, meiner Frau

Ich nehme wenige ehrwürdige Philosophen öfter

Es wäre mir wesentlich wohler auf Erden, wenn Sie den Ruhm der „Wiener Schule“ vermehren würden,

Schreiben Sie lang, belebt und belehrend, uns, die wir, der Weis

Ihr

O.N.

Alles Schöne zum Neuen Jahr! In den nächsten Tagen schreibe ich ausführlicher.

Fritz Waismann

Brief, hsl., 4 Seiten (kleines Format), RC 029-16-06; Briefkopf: hsl. 31. XII. 27; am Briefanfang Zeichnung eines Elefanten, am Briefende Zeichnung zweier ineinander verschlungener Drachen.

Example 3: Editor Text

Einleitung

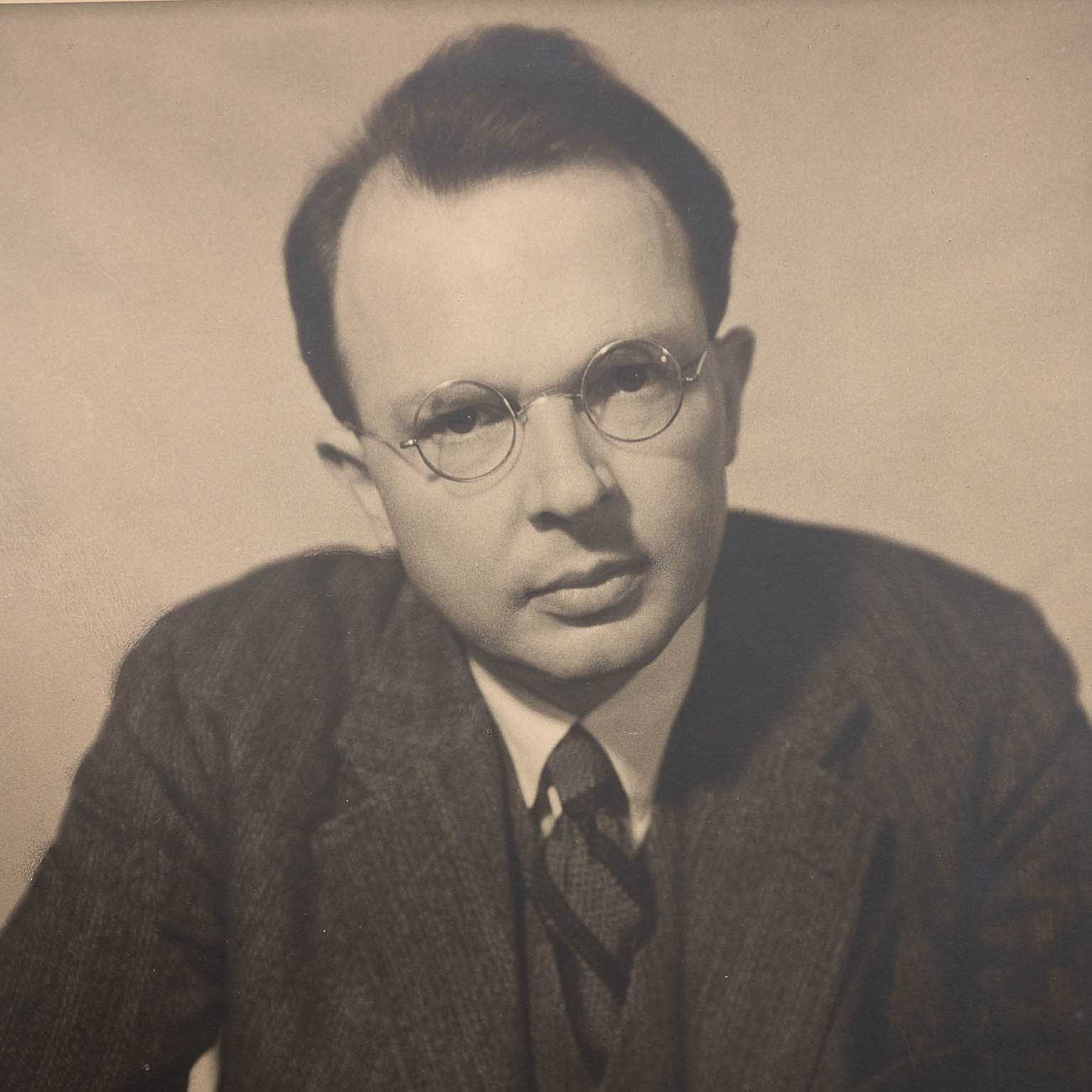

A. Zur Edition Schriften aus dem Nachlass von Rudolf Carnap

Carnap (1891-1970) war einer der wichtigsten Vertreter des Wiener Kreises und des Logischen Empirismus und damit Schlüsselfigur sowohl der europäischen Philosophie der Zwischenkriegszeit als auch der amerikanischen analytischen Philosophie der Nachkriegszeit. Dies, obwohl seine Schriften vor allem an ein akademisches Fachpublikum gerichtet waren. Mit dem Fokus auf streng wissenschaftliche Bearbeitung philosophischer Probleme, in seinem Fall unter Verwendung der mathematischen Logik, steht Carnap für eine Professionalisierung der Philosophie, die für die analytische Philosophietradition insgesamt charakteristisch ist. Dabei verliert die Philosophie zwar ihre Rolle in der Öffentlichkeit, sie hört deshalb aber nicht auf, praxisrelevant zu sein. So auch bei Carnap, wobei die politisch-praktische Seite seiner Philosophie erst vor dem Hintergrund der in den letzten Jahrzehnten begonnenen historischen Aufarbeitung sichtbar wird, die sich auf alle Aspekte seines Werkes stützt, unter Einschluss von Dokumenten aus dem Nachlass.

Die Philosophie Carnaps kann, in ihren hauptsächlich veröffentlichten Erscheinungsformen der Philosophie, als Sammlung von hochspezialisierten philosophischen Werkzeugen aufgefasst werden, denen keine Erläuterungen über die intendierte Verwendung beigegeben sind. Grund für diese puristische Gestalt von Carnaps Werk ist sein neusachlicher und radikal moderner Stil, den er in den 1920er-Jahren unter dem Einfluss des Wiener Kreises entwickelte. „Auch wir haben ,Bedürfnisse des Gemüts` in der Philosophie“, wie Carnap betont, „aber die gehen auf Klarheit der Begriffe, Sauberkeit der Methoden“,

Die mit diesem Band beginnende Edition Schriften aus dem Nachlass von Rudolf Carnap setzt sich die Publikation der Tagebücher, des Briefwechsels, der Manuskripte und Vorlesungen Carnaps zum Ziel, begleitet von einer Online-Edition der Faksimiles des Carnap-Nachlasses und der Pdfs der als Open-Source-Edition angelegten Druckedition auf VALEP. (Zu den formalen Richtlinien und dem Gesamtplan der Edition siehe den editorischen Anhang dieses Bandes.) Dieses Vorhaben steht in enger Beziehung zu der die veröffentlichten Schriften umfassenden, zweisprachigen Gesamtausgabe The Collected Works of Rudolf Carnap bei Oxford University Press.

Viele der hier publizierten Texte werden in dieser Ausgabe erstmals zugänglich gemacht. Bis vor wenigen Jahren waren die Tagebücher und die privaten Korrespondenzen für die Forschung gesperrt. Überdies sind viele der im Nachlass zu findenden Texte Carnaps (die Tagebücher und ein Großteil der Manuskripte) in Kurzschrift verfasst (vgl. Editorischer Anhang B.2). Transkriptionen dieser Texte liegen bislang nur zu einem kleinen Teil vor und werden in dieser Edition erstmals systematisch bereit gestellt und textkritisch abgesichert. Vor dem Hintergrund der oben formulierten Arbeitshypothese über die Rolle der unpublizierten Schriften Carnaps soll eine Neubewertung seines Werkes eingeleitet werden. Neue Gesichtspunkte für die Erforschung der Geschichte des Wiener Kreises und des Logischen Empirismus sollen erschlossen werden. Namentlich die hier begonnene Edition der Tagebücher ist jedoch über den engeren philosophiehistorischen Kontext hinaus von Bedeutung, als das zwanzigste Jahrhundert insgesamt repräsentierendes (kultur)historisches Dokument.

B. Zu den Tagebüchern Carnaps

Knapp 4.500~kurzschriftliche Seiten, auf denen über sechs Jahrzehnte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts dokumentiert sind: Die Tagebücher Carnaps stellen ein historisches Dokument von beeindruckendem Umfang dar (vgl. Editorischer Anhang B). Die ersten Einträge sind 1908, in Carnaps Wuppertaler Gymnasialzeit entstanden (TB 1). Es folgen in den Jahren des Studiums Carnaps in Jena und Freiburg einige verstreute Fragmente, Reisetagebücher sowie die umfangreichen tagebuchartigen Aufzeichnungen von Briefen Carnaps an seine Jugendfreundin Tilly Neovius (TB~3). Den Ersten Weltkrieg hat Carnap in einem hier ca.~200~Seiten umfassenden „Kriegstagebuch“ dokumentiert (TB 10 \hbox{--} TB~19). Ab 1920, in den in voraussichtlich vier weiteren Bänden vorzulegenden Tagebuchteilen, stehen Carnaps wissenschaftliche Aktivitäten im Zentrum. Im Zusammenhang damit dokumentieren die Tagebücher Carnaps Leben in einem bestimmten intellektuellen Kollektiv, das sich zunächst, von 1926 bis 1935, um den für Carnaps geistige Entwicklung entscheidenden Wiener Kreis gruppiert, dann, nach der Emigration und bis zu Carnaps Tod im Jahr 1970, von der internationalen Bewegung des Logischen Empirismus und der analytischen Philosophie gebildet wird. Die Tagebuchaufzeichnungen repräsentieren so, zunächst fragmentarisch, ab 1920 so gut wie lückenlos, über sechs Jahrzehnte von Carnaps Leben. Sie sind wichtig als autobiografisches und philosophiehistorisches Dokument. Darüber hinaus ist die kulturhistorische Dimension hervorzuheben, legen die Tagebücher doch, am Beispiel der vom Bruch der Emigration geprägten Karriere eines bedeutenden Wissenschaftlers, einen Schnitt durch zwei Drittel des 20.~Jahrhunderts und liefern damit eine alltagsgeschichtliche Fallstudie von bemerkenswerter Dimension.

Carnaps Tagebücher protokollieren das Tagesgeschehen aus der Perspektive des objektiven (Selbst-)Beobachters. Sie beschreiben, was der Autor im Tagesverlauf getan und erlebt hat. Die Tagebücher des reifen Carnap (ab Mitte der 1920er-Jahre) schildern das Leben in allen Facetten, von der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion bis zum Kinobesuch, vom Kaffehaustratsch bis zum Sex, vom politischen Ereignis bis zu den Schmerzen des Alltags, Schlaflosigkeit und Medikamentenkonsum. Die Perspektive ist jedoch stets die der positivistisch gedeuteten lebensweltlichen Erfahrung. Das heißt, es wird nicht einfach das ,Eigenpsychische` geschildert, sondern dessen ,fremdpsychischer` Anteil, alles also, was auch einem dritten Beobachter am Erleben Carnaps zugänglich wäre (zur Rolle des Eigen- und Fremdpsychischen in Carnaps Philosophie vgl. die Einleitung zum zweiten Band dieser Edition). Nie wird ein Ereignis anders geschildert als aus der Perspektive des objektivierten eigenen Erlebens. Im Tagebuch tritt zu diesem Erleben des Tages keine zweite Ebene des Reflektierens oder Entwerfens hinzu. Gefühle und Werthaltungen kommen nur insofern zur Sprache, als bestimmte Äußerungen von Gefühlen und Werthaltungen, so sie im Tagesverlauf stattgefunden haben, erwähnt werden. Das Tagesgeschehen wird protokolliert, aber es wird nie darüber reflektiert. Die Tagebücher enthalten keine Bekenntnisse, Beichten, Reflexionen oder Meinungsäußerungen. Historische Ereignisse kommen nur dann zur Sprache, wenn sie im Tagesgeschehen selbst eine Rolle gespielt haben, etwa wenn ein Heeresbericht im Kreis der Soldaten diskutiert wird; wenn Carnap den Brand des Justizpalastes oder die Studentenunruhen in Wien beobachtet; wenn eine Hitlerrede im Radio angehört wird. Philosophische Gedanken und Theorien spielen im Tagebuch nur indirekt eine Rolle. Zum einen, indem über die Arbeit an philosophischen Schriften berichtet wird, meist nur unter Angabe des Arbeitstitels, gelegentlich unter Hinzufügung des gerade behandelten Abschnittes oder Themas. Zum anderen, indem philosophische Diskussionen protokolliert werden. Philosophische Gedankengänge des Autors kommen nur dadurch zur Sprache, dass sie als Argumente in einer beschriebenen Debatte angeführt werden.

Die Tagebücher stellen somit keinen Bruch mit Carnaps eingangs erwähntem radikal modernen Stil dar, indem sie keine Freiräume schaffen für emotiven Diskurs. Sie sind, genau in dem technischen Sinn von Carnaps Auffassung über den „Ausdruck des Lebensgefühls“ darin, keine Dichtung, auch wenn sie in einem anderen Sinn als neu-sachliche (oder nach-expressionistische) Kunstform aufgefasst werden können (siehe Abschnitt B.1). Nichtsdestoweniger stellen die Tage\-bücher eine wichtige Ergänzung des publizierten Werkes dar. So kommen „praktische Entscheidungen“, Aussagen über moralische und politische Präferenzen und deren Kontext, in den Tagebüchern, anders als im wissenschaftlichen Werk, sehr wohl zur Sprache, wenn auch nur in der Gestalt der Protokollierung von Diskussionen, Aussagen, Entscheidungen und nicht auf der von Carnap vermiedenen Meta-Ebene der expressiven Reflexion. Die Tagebücher liefern unerlässliche Informationen zu Entstehung, Hintergrund und Motivlage von Carnaps Werk. Man kann sie als kontextualisierende Erläuterungen zu seinen publizierten Schriften lesen.

In engem Zusammenhang mit dieser auf Carnaps philosophisches Werk bezogenen Perspektive erfüllen die Tagebücher eine wichtige Rolle als Dokumentation seiner intellektuellen Biografie und zur Geschichte des Wiener Kreises und des Logischen Empirismus insgesamt. Hier stellen sie eine einzigartige Primärquelle dar. Das gilt besonders für die Zeit Carnaps im Wiener Kreis von 1926 bis 1935. In keiner anderen literarischen Quelle wird ein so lebendiges Bild der Aktivitäten des Wiener Kreises gezeichnet.

Selbst wenn die so umrissene dokumentarische Perspektive für die philosophiehistorische Forschung den wichtigsten Gesichtspunkt der Tagebücher darstellt: ihre Bedeutung als historische Primärquelle erschöpft sich nicht darin. Gerade in dem hier vorgelegten ersten Band der Tagebücher spielt die philosophiehistorische Perspektive eine eher untergeordnete Rolle. Carnap hat die Entscheidung für eine akademische Karriere erst recht spät, im Jahr 1920, getroffen, die Annäherung an die Wiener und Berliner Szene um Moritz Schlick und Hans Reichenbach erfolgte ab 1922. Nach Wien übersiedelte Carnap erst 1926. Deshalb dokumentieren die in diesem ersten Band versammelten Teile der Tagebücher, die hier immerhin gut 400~Seiten umfassen, Aspekte in Carnaps Leben, die mit der akademischen Philosophie nur am Rande etwas zu tun haben. Im Zentrum stehen vielmehr zum einen die Aktivitäten Carnaps in der deutschen Jugendbewegung, zum anderen seine Erfahrungen im Ersten Weltkrieg.

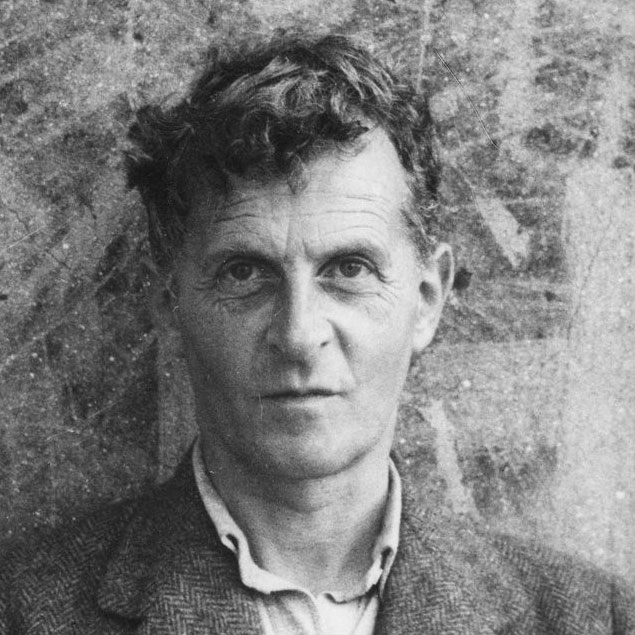

Carnaps Tagebücher können daher in einem allgemeineren, aber, wie sich zeigen wird, mit dem philosophiehistorischen eng verknüpften \emph{kulturhistorischen} Sinn gelesen werden, als \emph{on-the-fly} erarbeitete dokumentarische Erzählung. Die sich aus dem Gesagten ergebenden Gesichtspunkte der Tagebücher Carnaps werden im Folgenden eingehender behandelt. Zunächst werden sie in ihrem Status als Literatur untersucht, wobei im Zentrum der von Carnap in den 1920er-Jahren erarbeitete neusachliche Stil steht (Abschnitt~\ref{sec:intro.B.1}). Dann wird als zentrales philosophisches Element der Tagebücher deren Funktion als Dokument radikal moderner Lebensreform und nonkognitivistischer Wertauffassung präsentiert (Abschnitt~\ref{sec:intro.B.2}). Schließlich werden die Tagebücher Carnaps zu denen seiner Zeit\-genossen in Beziehung gesetzt, wobei Carnaps radikal moderne Haltung weiteres Profil dadurch erhält, dass sie sich als Alternative auffassen lässt zu Einstellungen wie denen von Ludwig Wittgenstein oder Martin Heidegger, in denen die Moderne abgewiesen wird (Abschnitt~\ref{sec:intro.B.3}).

1. Die Tagebücher als Aneignung einer neusachlichen Kunstform

Um Carnaps Tagebücher sprachlich angemessen einzuschätzen (vgl. auch die Bemerkungen zu Carnaps Verwendung der Kurzschrift im editorischen Anhang,~\hyperref[kurzschrift]{B.2}), ist die grundsätzliche Frage der literarischen Qualität seiner Texte zu stellen. Dies gilt umso mehr, als Carnap bis heute als Antithese gesehen wird zu den literarisch anspruchsvollen „Dichterphilosophen“, von Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche und S\o ren Kierkegaard bis Wittgenstein. Diese Einschätzung hat etwas für sich: Es ist eben das Charakteristische an Carnaps Ausdrucksweise, dass sie sich der Expressivität verweigert, die bei den sogenannten Dichterphilosophen im Zentrum steht. Bloß bedeutet diese Haltung nicht zwangsläufig auch, dass Carnaps Texte ohne literarischen Anspruch sind.{\tolerance500\par}

Die frühen Tagebücher, bis Mitte der 1920er-Jahre, sind, mit Ausnahme der Tilly-Briefe (TB~3) und der Kriegstagebücher (TB~10 \hbox{--} TB~19), in denen umfangreichere Schilderungen zu finden sind, eher im Telegrammstil gehalten. Es geht wie in den Tagebüchern Goethes, Albrecht Dürers oder Lion Feuchtwangers um Stichworte, die Tagesereignisse protokollieren. Einen literarischen Anspruch erheben diese bloß mnemotechnischen Notizen nicht. Um die frühen Tagebücher als Äußerungen von Carnaps Stil richtig einzuschätzen, ist es daher wichtig, jene raren Stellen herauszugreifen, die mit einer erkennbaren schriftstellerischen Intention formuliert sind. Das gilt für die tagebuchartig aufgezeichneten Briefe an Tilly Neovius~(TB 3). Auch die Beschreibung des jugendbewegten Sommers 1912 (Tagebuch 5) ist ambitioniert. Vgl. beispielsweise die Erzählung über die „Blutsbrüderschaft“ mit Carnaps späterer erster Frau Elisabeth Schöndube am 31. VII. 1912:

Sie reicht ihren rechten Arm. Ich ziehe mit der krummen Spitze einen Schnitt, immer wieder, fest hinein. Sie ist tapfer und hilft die Haut halten, bis Blut kommt. Das küss ich ab. [\ldots]~-- Mir saust's durch den Kopf: Jetzt Mut, entscheiden! [\ldots] Jetzt einmal stark sein, nicht leicht~-- Genuss~-- zufrieden. Atemholen. „So, jetzt müssen wir uns auch küssen.“ Sie gibt ihr Gesicht und lässt sich küssen. [\ldots] Wir küssen uns wieder. Sie lehnt an mir. Oh, wir zwei.

Markant ist auch die Darstellung der „Kämpfe am Winterberg“ vom 5. bis 9. V. 1917 (Tagebuch 18), hier die Passage, die Carnaps Verwundung schildert:

Das wahnsinnig dichte Pfeifen um unsre Köpfe hat etwas nachgelassen, drum wagen wir alle, den Kopf herauszustecken und sehen hellblaue, lange Franzosenröcke und zwar von hinten. Und da schießt natürlich alles wieder mit Feuereifer.~[\ldots] Plötzlich ein Schlag vor den Kopf, ich taumele zurück, Blut läuft mir übers Gesicht. Ich nehme den Stahlhelm ab: Er hat ein hand\-langes, zackig gerissenes Loch. Während ich in Eile mein Verbandpäckchen auspacke, schwebt mir ein Bild vor, das ich vorgestern gesehen: Ein sterbender Mann, seitlich auf Gepäck oder Leichen liegend, sodass der Kopf frei hängt, aus einem Loch in der Schläfe strömt das hellrote Blut wie ein Brünnlein herab~[\ldots]. Würde ich auch bald so liegen?

Erst in den 1920er-Jahren beginnen die Tagebücher das Leben in dem intellektuellen Kollektiv Carnaps zu dokumentieren, indem immer mehr die präzise Schilderung von Gesprächen in den Vordergrund tritt sowie im Zusammenhang damit eine der Neuen Sachlichkeit nahestehende Ästhetik kultiviert wird. Diese stilistische Entwicklung fällt zeitlich zusammen mit der Übersiedlung nach Wien und dem Eintritt Carnaps in den Wiener Kreis um Moritz Schlick und Otto Neurath sowie mit den durch Franz Roh vermittelten Kontakten zur Bauhaus-Szene um Sigfried Giedion, Carola Giedion-Welcker, Lucia Moholy und László Moholy-Nagy. Diese Strömungen konvergieren bei Carnap nicht nur in der Philosophie des \textit{Aufbau}, sondern auch in einer neuen literarischen Ausdrucksweise, die er etwa zwischen 1925 und 1935 entwickelt und die verblüffend nahe steht zu der von Roh als Chronist und Propagandist mitgeprägten Kunstform der Neuen Sachlichkeit bzw. des „Nach-Expressionismus“, wie sie von Roh selbst zunächst bezeichnet wurde. Roh hat in seinem stilprägenden Manifest gleichen Titels Carnap, wenn auch ohne Namensnennung, als charakteristischen Typus aufgenommen: der ,rationale Mensch`, der ,Fugenschreiber der Logik`, der ,ausdrucksbewußte Ingenieur` und ,Maschinenbejaher`, „womit ein neuer, synthetischerer Typus von Praktiker geschaffen wäre“.

Christian Damböck: Editorial Principles for VALEP

Some notes on \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML5

How to get from \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) to HTML5 (and TEI-XML)

Graphic and semantic text processing

Both HTML and \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) offer the possibility of processing text with semantic markup, which means that a text is provided with tags that indicate all kinds of semantic properties (see below for more details on the exact meaning of semantic text processing). This job can be done using HTML or TEI-XML or \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\). The differences are not at the level of semantics but at the level of the media used. \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is intended for processing text on printed pages, HTML is intended for processing text on a screen, and TEI-XML is open to both simply because it has no intended medium at all (more on TEI-XML later in this document).

To understand that \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML offer quite similar things at the semantic level, it is important to see that \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is also a markup language, because unlike \(\mathsf{\TeX}\) it does not have the sole purpose of functioning as an electronic typesetting machine. In a sense, what \(\mathsf{\TeX}\) provides for \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is similar to what CSS and Javascript do for HTML. What makes the relationship between layout and markup more transparent in the case of HTML is that HTML allows itself to be nothing more than a language for semantic markup, while all the graphical and layout stuff is done in CSS and Javascript. In the case of \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) the distinction between different interfaces is less clear because \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and \(\mathsf{\TeX}\) commands are lumped together. But even here, the intent of \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is clearly to provide the ability for semantic markup and to keep that separate from all the layout stuff, which is then done at the more basic level of \(\mathsf{\TeX}\). \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) macros like \chapter or \emph and the corresponding HTML tags <h1> and <i> are semantic in the sense that they say that the text they contain is a header or something that the author has highlighted, i.e., they reproduce some intentions of the author. This can be refined to any degree in customizing \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) macros and HTML tags that have very specific semantic meanings (see the section on standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and text critical markup below).

Scientific editions produce primarily semantic markup

The key point for the present observations is that the idea of a scientific or critical edition (in comparison with mere typesetting or web design) is that it primarily takes care to the semantic layout of the edited text and primarily tries to reproduce this layout, while all kinds of graphical stuff plays only a secondary role. This does not mean that graphics is unimportant here and it certainly does not mean that scientific or critical editions are necessarily uglier than others. It only means that the editors always first try to understand the text, categorize, describe and comment on every portion, while during that process they intend to care little or not at all about graphics. In many cases, the graphics is done by a different part of the editorial team - the type setters and design specialists - and the editors need not to worry about graphics at all.

And this whole story has important consequences for the task of conversion from \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) to HTML or TEI-XML, and of course for the ways in which the respective dialect that is used here at the level of \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\), HTML or TEI-XML is to be firstly specified. It is not particularly relevant at all, which language is used as a starting point, for they are all markup languages that can be arbitrarily customized. The point is that there must be a nomenclature, ideally represented in macros, tags, and classes, which all have a quite specific semantic meaning and therefore can be easily translated from one markup language to another. Here are some examples for semantic categories that straightforwardly can be represented in semantically identical \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) macros and HTML or XML tags:

- Header for a particular diary convolute or a particular letter

- Label of a particula diary entry

- Sections of letters: salutation, main part, signature, enclosures

- Any other kind of sections and paragraphs

- Text markup: underlinings, insertions, deletions, editor additions

- Footnotes or marginal notes by the author and notes that contain comments by the editors

- References (indices) to persons, institutions, locations, events, published and unpublished work, web resources, etc.

The list is incomplete but it is important that it does not contain things like "times new roman font, 12pt, color lightgrey, left margin 3ch, etc. etc." First, these things might be different in a presentation of the material on a printed page, in a browser window, or in a database. Second, these things have in most cases nothing to do with the original text and/or the intentions and references of the author being associated with it. Semantic markup exclusively addresses the latter, while the graphical layout is mainly produced at the level of macro-definitions in \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) or CSS and Javascript specifications (in HTML) for the pre-defined semantic macros, tags, classes, and attributes.

Universally valid semantic conversion plus proprietary graphical layout

In principle, the semantic categories of an edited text can be easily represented in either \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) or HTML or (TEI-)XML, for these languages are all sufficiently flexible, including features such as the following:- Custom names for all relevant macros, arguments, or attributes

- Aritrary complexity: one macro or tag can have any number of arguments

- (Almost) infinite flexibility in the ways in which any semantic token is graphically interpreted

The only restrictions at the graphical level that apply here are the obvious ones: \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) produces graphical output on pages for print, while HTML produces graphical output on a screen, more presicely, in a browser window. TEI-XML, unlike \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML, is not restricted to a specific form of media. It at least in theory offers a mere semantic text specification, which then can be customized for print and screen output tasks. But TEI-XML also suffers from obvious restrictions that overcompensate this advantage:

- The specification is terribly complex and indefinite, for it offers vast numbers of different strategies to achieve the same semantic markup with quite different XML statements, using entirely different TEI-XML tags and attributes

- The "standard" is parochial and actually represents a relique of the earliest days of XML and the web

- Standard solutions for processing \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML exist, whereas TEI-XML is typically handled in proprietary software that might be no longer available in a couple of years

- TEI-XML might be dead soon but \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML are so widespread that one can assume they will exist as living standards as long as computers exist

- As soon as we arrive at the task of graphical layout on pages or screens we also arrive at the situation that the standards we need are, again, CSS and Javascript (for screens) and \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) (for printed pages), so why don't we start with one of these standards in the first place?

- Most importantly, it is ultimately irrelevant which markup language we use, as soon as our overall layout is semantically consistent

So, the proposal would be to start with any useful standard, and then program suitable scripts to transfer the semantic information from one standard to another. We definitely need \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) and HTML and the beforementioned assets of them as well as the downsides of (TEI-)XML might involve that the best idea would be to use any of the two as a starting point, but in principle even (TEI-)XML would do the job.

This project: \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) ➵ HTML

We chose \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) as the primary language for this project for several reasons that include:

- \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) sources are much more easily written and read by humans than sources in HTML or TEI-XML

- Logicians use \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) for typesetting formulas and therefore can use the text processing language they know best

- It is the most precise and consistent way to write source code directly, rather than using WYSIWYG software

- The printing task needs much more intervention than the screen presentation task, therefore the \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) code is typically richer than its HTML equivalent

Editorial principles

Formulas with mathjax

HTML does not offer a suitable solution for presenting formulas. The only possibility is to use \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) or MathML, together with a Javascript package that transforms theses sources in vector images. The best solution that exists, namely mathjax, simply produces a vector image from \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) code and includes it in the HTML code. Mathjax also takes care to the semantic structure of the formula, or at least those semantical aspects of the formula that are straightforwardly syntactical, because it reproduces the formula also in the markup language MathML and includes this in the code: just right click on one of the example formulas below. This is one of the most complicated formulas in the Aufbau, §119, here reproduced from the typesetting done by Richard Zach for the collected works. I only had to replace the macros with some standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\), but this can be easily improved later. This is standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) processed with mathjax:\(\exists Q,\nu). \mathsf{3}\ \mathsf{Dzhomum}\

(\breve{\varepsilon}|Q|\varepsilon) \downharpoonright \hspace{-8px} \upharpoonright \mathsf{Aeq}'

\{\hat{\alpha}\hat{\beta}((\exists\varkappa,\lambda,\mu).

\varkappa\breve{\varepsilon}|Q|\varepsilon\lambda.\varkappa\breve{\varepsilon}|Q|\varepsilon\mu.\)

\(\lambda\breve{\varepsilon}|Q|\varepsilon\mu.\varkappa,\lambda,\mu\varepsilon\hat{\xi}\{\exists

!\xi:(\exists\varrho).\varrho\varepsilon\nu.\xi = \varrho -

s'(\nu-[\varrho])\}.\alpha\varepsilon\varkappa.\beta\varepsilon\lambda.\)

\(\mu\cap\overrightarrow{Q}

'\alpha=\mu\cap\overrightarrow{Q}'\beta)\}_{po}.\nu

= \mathsf{Sim}'((\mathsf{Fr} \cup \mathsf{I}) \downharpoonright \hspace{-8px} \upharpoonright \hat{\alpha}

\{(\exists\mu).\mu\varepsilon \mathsf{Aeq}' Q_{po}.\)

\(\mathsf{Dzp}(\mathsf{5},\mu,\alpha,\mathsf{Umgr}' Q)\}). Q

=\hat{\alpha}\hat{\beta}

(\alpha,\beta\varepsilon\hat{\zeta}\{(\gamma):\gamma\varepsilon

\mathsf{Sim}'(\mathsf{Er}\cup \mathsf{\breve{Er}}\cup

\mathsf{Er^0}).\)

\(\mathsf{Nc}'(\zeta\cap\gamma)\diagup

\mathsf{Nc}'\zeta>\frac{1}{2}.\ni.\zeta\subset\gamma:.

(x):x\sim\varepsilon\zeta.\ni.(\exists\delta).\delta\varepsilon

\mathsf{Sim}'(\mathsf{Er}\cup\)

\(\mathsf{\breve{Er}}\cup \mathsf{Er^0}).\alpha\subset\delta.

x\sim\varepsilon\delta\}.\alpha\uparrow\beta\subset

\mathsf{Er}\cup\mathsf{\breve{Er}}\cup \mathsf{Er^0})\) (5)

The only issue here is that the line break is not automated. Instead the paragraph is fixed to 600px, which means that if the window is getting too small the text hovers out of the margin. Similar problems arise when the font-size is getting increased (try it with the plus button in the menu bar). But there are certainly ways to fix these issues. Currently the line-breaks exactly resemble the line breaks in the original edition.

In his later writings Carnap is using modern math notation which can be even easier reproduced, no matter how complex the formulas are. Again, mathjax interprets all math that is written in standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\), together with all available standard classes such as amsmath etc. An example from Logical Foundations of Probability, p. 334:

\[\mathfrak{c}(i,e)=\mathfrak{c}(h,e)+\sum_{p=1}^{n}[\mathfrak{c}(h_p,e)\times\mathfrak{c}(i,e.h_p)]\]To conclude: whatever one can get in \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) can also be achieved in HTML without restrictions at the level of typesetting. The only technical restriction is that all custom macros must be removed first and replaced with standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\), but this is not a problem at all and also makes the formulas more readable.

A note on Unicode

\(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is a very old markup language that was basically developed in the 1980s and hardly changed over the previous three decades. In some respects there is simply no need for making any further changes to it. HTML5 and CSS3 are also standards that now exist for more than 10 years and will hardly be changed too much in the future. The most obvious aspect, however, where \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) must be considered a very old system is that it is notoriously based on the standard repertoire of ASCII, i.e., lowercase and uppercase latin letters and arabic numbers. Though there are extensions for \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) that allow the use of at least parts of Unicode, these extensions are not as stable that one might be able to straightforwardly use Unicode in \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\). Therefore, one of the more tedious sides of conversion from \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) to HTML and other varieties of XML is to transfer all those idiosyncratic \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) macros that transfer some Unicode symbols to ASCII code to Unicode again. However, the use of idiosyncrasies like \glqq/\frqq and \grqq/frqq for German „“ and French »« quotation marks or \"a for ä, \"s for ß or \o for ø or \, ~ \! etc. for different varieties of white space or - -- --- for different varieties of hyphens are not just weird ways of hopeless nerds to produce illegible text. They also have a great advantage, namely, that insiders never can mix up different symbols, whereas Unicode varieties quite often cannot be graphically identified at all without looking up the exact Unicode identifier. Thus, \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) is a great tool for typesetting portions of Unicode, without being dependent on clumsy Unicode generating software.

Semantic markup: the details

Most standard \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) macros for typesetting headings, text emphasis and the like either have natural expressions in HTML or, as in the case of formulas, are simply reused in HTML without changes. But since the semantic accuracy of the \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) we use is very high we need customized macros and HTML tags that deal with this more specific semantic content. This section provides an overview of semantic markup as being used here.

Editor text versus author text

The most high level but no less crucial distinction the semantic markup of an edition must offer is to consistently distinguish between text that is written by the edited author and text that comes from the editors. In HTML we define two classes author and editor for that purpose. Graphically, the rule is that author-text is always typeset in a serif font (here Libertine) and editor text in a sans serif font (Biolinum). If author text shows up inside of a flow of editor text it is additionally highlighted with angle brackets, which is useful since Libertine and Biolinum are quite similar and the serifs in Libertine are rather subtle.

Customized headings

The headings as to be found in the example texts below are all customized in ways that the used macros or class identifiers already indicate what kind of text the section heading is opening: a diary convolute, a diary entry, a letter, the heading, main part, signature, enclosures, or editorial appendic of a letter, etc. These things are important to note because in many cases there is no explicit graphical representation at all that distinguishes the section from others: the semantic meaning is defined either by the context or, explicitly, by the respective macro, tag, or class descriptor.

Notes, indices, facsimiles

There are several types of notes which are represented in \(\mathsf{\LaTeX}\) as footnotes or marginal notes. In HTML the strategy is that all material that comes from the author is represented directly inside of the main text box as marginal notes, whereas all editor notes are represented optionally as marginal notes in the grey area on the right (which is not available on smaller screens) or as socalled tooltip notes. (Use the menu button with the horizontal arrow to shift between these two options.)

Notes by the author

A passage of author text may contain either footnotes by the author.

Text that is put in the margin by the author or represents portions of the text that the editors want to highlight for some reason - in the case of the diaries the respective location where entries are written is highlighted in this way - and it is put in a highlighted box without symbols.

Editor notes, indices, and facsimiles

The editors can insert notes on the semantic status of a text in various ways. The most common way is just to insert a note with explications and editors comments.

In addition to these more informal notes whose content may heavily vary, an edition may also contain more formally structured indices. These include references to persons

Different appearances of the screen: dynamic HTML

An obvious asset of HTML is its dynamic nature. This editorial strategy includes several dynamic aspects. Apart from links and references to VALEP and other online resources that can be entered with a mouseclick, the appearance of the screen also can be dynamically manipulated. Just try this on the menu in the upper right corner. You can present notes optionally in the right margin or as popup notes (the former feature is available only on screens wider than 600px). You can increase or decrease the font size. And you can entirely hide notes and texcritical markup, in order to see the original text of the author and nothin else. Additionally, there is a button that will provide a pdf version of the text for download and a fullscreen version which is useful particularly in cases where the HTML source is presented on a small window inside of the user platform of VALEP.

Textcritical markup

Since textcritical markup shows up only in text written by the edited author, we shift to Libertine here. These are the most important cases for textcritical markup that identifies semantic properties of the text in ways that are graphically represented here in quite similar ways in the printed and screen version:

| Tag name | Text critical meaning and graphical representation |

<u>, <i> |

In the diaries: Text that is underlined (or highlighted) by the author and text that was written in longhand by the author (in passages that are mainly written in shorthand) |

<del> |

Text that is |

<del class="editor"> |

Text that is |

<ins class="author"> |

Author text that is inserted in passages of editor text or |

<ins class="editor"> |

Text that is inserted by the editor inside of text of the author |

<ins class="later"> etc. |

Text that is inserted by the author later as well as text that is underlined by the author later or |

<un-certain> |

Text where the transcription is uncertain in some ways |

<text-ill> |

There are marks for illegible words |

<text-hooks> |

Text that is |

<text-rep> |

Text that is indicated by the author using repetition signs such as " and is |

<text-gap> |

A gap in the text |

<sub>, <sup> |

Text that was written as supscript or superscript by the author |

VALEP Documents

Document listing

...

Document listing

The Documents in the list include all metadata plus filter options.

Click on the document opens the document view (lower document window in VALEP)

- The Filter window shows the content of the lower document window

- The main window (= this window) switches to content view and shows one of the following things:

- The HTML view (first priority), see the example below

- The pdf (second priority) in the image viewer (cf. "Archives")

- The facsimiles (third priority) in the image viewer (cf. "Archives")

- If the document contains only metadata there is no document view option available

Example document in HTML view:

Metadata Window:

Image Viewer

VALEP Persons

Person 1

Person 2

...

VALEP Institutions

Institution 1

Institution 2

...

VALEP Concepts

Ontologies

Carnap ontology

Concept 1

Subconcept 1

Concept A

Concept B

...

A read only version of VALEP Locations:

Standard Locations Special Locations

World

Europe

Austria

Lower Austria

Baden

Mödling

...

Hosts, Sponsors, Cooperation Partners: all Logos are also displayed here

VALEP Prototype

© 2024 by Christian Damböck